It Takes a Whole Village to Raise a Child

I used to fantasise about being a hermit. All of my problems

would be solved, I thought, if I could just be left alone — by people and the

world. For, all of my ailments and stress were caused by others...obviously!

Family, friends, strangers, social conventions, conventional morality,

government...and most probably you too. It made perfect sense, to my mind. It

was scientific even. Like when two inert substances are brought together, such

as bicarb soda and vinegar, you get an acidic, frothing, bubbling over

reaction. My life was a continual series of these kinds of chemical reactions.

But, if you keep the substances apart...peace and serenity… Genius! Nobel Peace

Prize please…

However, as a friend of mine would annoyingly point out

whenever I bemoaned my inability to extract myself from society and enter the

serene utopia of Thoreau’s ‘Walden’, “If you really wanted to be living that

life, you’d be doing it”. Damn him and his beautiful logic! I may not have accepted

it at first, but sometime later it resonated with me. Of course, it wasn’t

other people I wanted to escape, it was my pain and ultimately myself. I

couldn’t see it at the time though. And when I did see it I didn’t accept it on

a deep, internal level straight away. For, I couldn’t see outside of my own

suffering, nor could I at that time observe the supportive architecture all

around me to be able to acknowledge the power available to me. And, funnily

enough, it was in fact society and other people that intermittently alleviated

my existential malaise. I would eventually come to internalise what I now call

‘radical self-responsibility’ (more about that in a future blog post). But in

the meantime I seemed to need to experience it, not just know it.

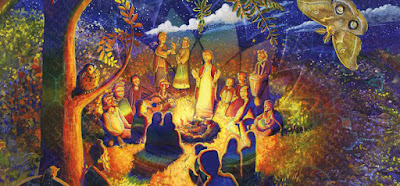

“It takes a whole village to raise a child”, so says the

African proverb. This resonates with me deeply and based on my own experience

and observation it is self-evident. For our earliest development to be healthy,

holistic and adaptive we require the care and input of more than just our

immediate family, but rather the greater community. Although, our modern day

communities are comprised more of schools, film, television and the internet

rather than kinfolk, nature and the oral tradition. And despite where the

community influence comes from and how it is delivered, the quality can’t be

guaranteed. Nevertheless, the village proverb seems an apt metaphor for, not

just our childhood development, but our whole of life development too.

Humans are social creatures and have been for hundreds of

thousands of years. We have relied on the clan, both socially and

psychologically, for so long it’s hard wired into our DNA. Individualism is but

a drop in the ocean in our evolutionary history, but has changed how we live in

the world and how we experience it and ourselves. It has brought about amazing

progress to our existence, such as challenging our assumptions about power and

possibility. It has also produced many new conditions in the human condition,

both psychological and social. Mental illness, the breakdown of social

reliance, Donald Trump, to name just a few. There is a theory that during and

post-World War II, wartorn Western societies experienced significantly greater

meaningfulness and S a result more robust, real happiness in their lives, despite the obvious trauma and

suffering. Counter intuitive, I know. The suggestion is that the coming

together of communities — albeit thrust upon them by unforeseen circumstances —

to rebuild their homes and societies and to support one another through their

adversity gave people’s lives enriched purpose and meaning. Alone, those

affected could not have achieved anywhere near what was achieved collectively.

And some of those directly affected by the horrors of war — the “collateral

damage” so to speak, the soldiers on the front line — were soothed and able to

recover faster and more robustly thanks to the sharing of their experiences,

their grief and the sharing of their stories.

Building community and relationships is like doing a load of

washing. All of the dirty laundry — the shirts, the towels the socks — are

thrown in together to be cleaned. During the wash everything mixes together,

rubbing and massaging each other into cleanliness. The dirt is shared around a

bit until it eventually washes away. The closeness may be a little forced,

sure, but the magic happens in spite of this, or perhaps because of it. If the

clothes were conscious I'm sure they'd resist a wash as much as I’ve resisted

change when at the crossroads of suffering (I think I’ve just uncovered the

mystery of the missing socks). To change or to stay the same...this is the

question. But at the end of the wash everything comes out clean and fresh.

Almost like new. Some still carry the remnants of stains that will take a few

more washes to expel. But the change is invariably unmistakable.

The sharing of our dirt is important to our transformation.

Usually anyhow. So much happens in this process that is valuable to our growth

process. Primarily it is the power of connection through story and by being

vulnerable, even when our deepest feeling says no, don't trust. Of course, it

isn’t always necessarily beneficial, and can in fact be harmful, to

indiscriminately share our “stuff” with just anyone or everyone. The checkout

operator at Woolworths doesn’t actually want to know how you really are.

Believe me, I’ve tried. Sharon on checkout three’s blank stare left me feeling

a little hopeless and abandoned, my vulnerability battered and bruised. So,

please choose your community wisely.

From a place of vulnerability we are open to the new and we

are open to learning and growth. “In the beginner's mind there are many

possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few” said zen master Shunryu

Suzuki in the zen bible, Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind. When I hold on too tightly

to my preconceived ideas about myself and the world there is little room for

expansion. My ego needs reassurance of the status quo for its security and

strength. But this is a myth, a story, one that we keep telling ourselves again

and again, into solidity.

Through our stories we find connection. And validation too.

When I’m vulnerable and in unfamiliar territory the soothing knowledge of

others wandering those lands too is a powerful remedy. Like being stranded on a

deserted island, the first sign of rescue is enough to lift our spirits and

instill us with hope. But too long in isolation and we find ourselves, like Tom

Hanks in Castaway, creating imaginary lifeforms to alleviate our suffering. So

too, we tell ourselves stories or myths rather than addressing the truth of our

underlying hurt. We seek solace in our pain and shut others out from it as a

kind of protective measure. And if nothing changes, nothing changes. We often

choose the familiarity of our suffering rather than the dark corridor of the

unknown. But it is through this corridor that can lead us to transformation and

salvation.